Walk through any modern steel mill, and you won’t see ingots of gleaming silver metal labeled “calcium.” Yet, in the final, crucial stages of producing high-quality steel, metallic calcium performs what can only be described as industrial alchemy. It is a secret weapon, a microscopic surgeon that operates within the fiery heart of molten steel to bestow strength, purity, and workability. This article explores the indispensable, behind-the-scenes role of calcium-based materials in steelmaking.

The Problem in the Melt: Unwanted “Inclusions”

To understand calcium’s role, we must first identify the enemy: non-metallic inclusions. During steelmaking, elements like aluminum are added to remove dissolved oxygen (a process called deoxidation). This creates solid byproducts, primarily alumina (Al₂O₃). While the oxygen is gone, these alumina particles remain suspended in the liquid steel like microscopic shards of ceramic.

If left untreated, these inclusions cause major problems:

Clogging: They solidify in the narrow nozzles of the continuous caster, disrupting production.

Weakness: In the final product, they act as stress concentrators—tiny cracks waiting to propagate—reducing toughness, fatigue resistance, and ductility.

Poor Machinability: They rapidly wear down cutting tools during machining.

The Calcium Solution: An Elegant Transformation

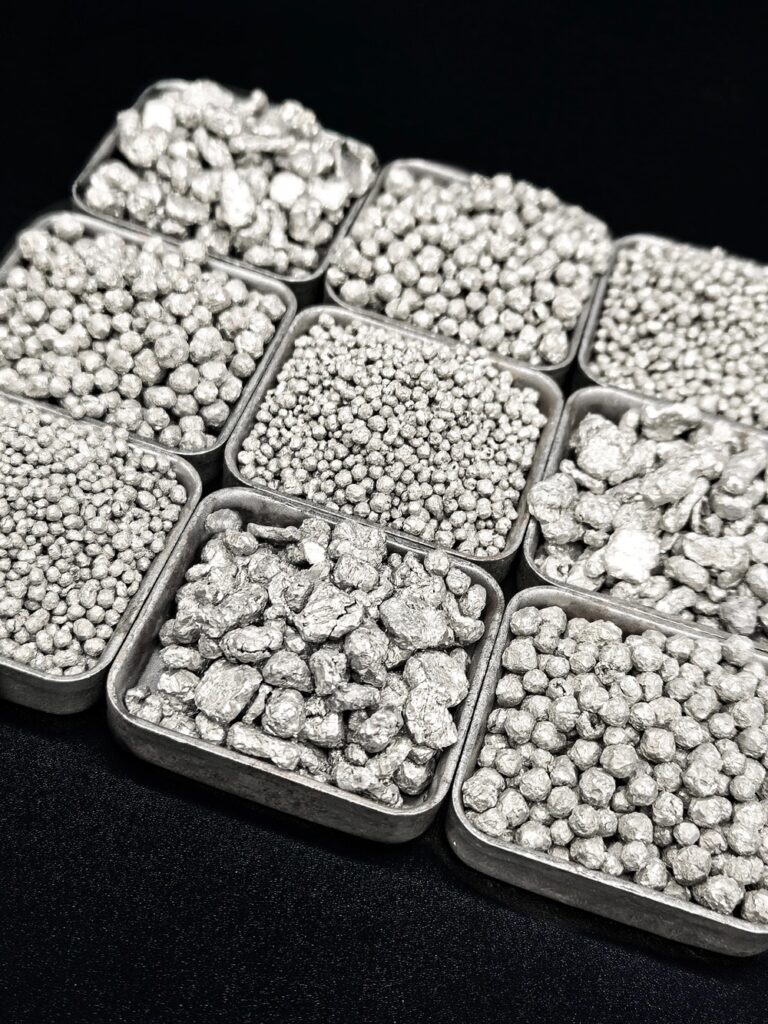

This is where calcium enters the stage. Steelmakers do not add pure calcium metal directly. Instead, they use it in two engineered forms:

Calcium Silicide (CaSi): A brittle alloy containing about 30% calcium.

Pure Calcium Cored Wire: A steel sheath filled with fine calcium powder.

The delivery method is as critical as the material itself. Using a high-pressure wire injection system, a precisely measured length of CaSi or cored wire is plunged deep into the ladle of molten steel (in a process stage aptly named “calcium treatment”).

Here’s the alchemy that follows:

The steel sheath melts, releasing calcium deep below the surface.

The calcium vaporizes (its boiling point is 1484°C, lower than steel’s temperature of ~1600°C). Bubbles of calcium vapor rise through the molten steel.

As they rise, these vapor bubbles aggressively react with the solid alumina inclusions. They perform inclusion morphology control, chemically modifying the alumina.

The hard, jagged alumina clusters are transformed into liquid or soft, globular calcium aluminates. This change is revolutionary:

| Property | Without Calcium | With Calcium Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion Shape | Jagged, solid alumina clusters | Soft, spherical calcium aluminate droplets |

| Caster Nozzles | Prone to clogging | Flow remains smooth and uninterrupted |

| Final Product | Lower toughness, poor ductility | Improved machinability, fatigue life, and formability |

| Anisotropy | Mechanical properties vary with direction | More isotropic, uniform properties |

The Multifaceted Benefits for Steel Companies

For a steel producer, implementing calcium treatment is not an extra cost but a strategic investment that pays dividends across the operation:

1. Enhanced Product Quality & Grade Capability:

This is the primary driver. Calcium treatment is essential for producing:

High-Grade Linepipe Steels: Used for oil and gas transmission, requiring extreme toughness in harsh environments.

Advanced Automotive Steels: For critical safety components like suspension parts and chassis, where fatigue resistance is paramount.

Heavy Plate Steels: For construction, shipbuilding, and mining equipment.

Wire Rod for Tires: The improved ductility is vital for drawing steel into the ultra-fine cords of steel-belted radial tires.

2. Dramatically Improved Production Efficiency:

By preventing nozzle clogging at the continuous caster, calcium treatment ensures a smooth, uninterrupted casting sequence. This reduces downtime for nozzle changes, minimizes breakouts (catastrophic leaks of molten steel), and significantly increases caster productivity and yield.

3. Superior Machinability for Customers:

The soft, globular inclusions act as built-in lubricants during machining (turning, drilling). This allows customers to machine parts faster, with less tool wear, better surface finishes, and lower power consumption—a major selling point for steel used in automotive or machinery manufacturing.

4. Desulfurization Boost:

Calcium also reacts with sulfur, another harmful impurity, to form calcium sulfide (CaS), which floats into the slag. This provides a secondary desulfurization, helping produce ultra-low sulfur steels for critical applications.

The process is not without its challenges. Calcium has a very low solubility in liquid steel and high vapor pressure, meaning its yield (the amount that effectively reacts) can be variable. Too little calcium has no effect; too much can lead to nozzle clogging from excess calcium aluminates or damage refractory linings. Therefore, success depends on precise control of:

Amount: Calculated based on steel grade and aluminum content.

Depth of Injection: Must be sufficient to allow time for reaction.

Wire Feed Speed & Temperature: Tightly managed process windows.

Conclusion: The Unsung Hero of Steel

In the grand narrative of steelmaking—from towering blast furnaces to roaring converters—the calcium treatment stage is a quiet, precise, and clean operation. Yet, its impact is profound. Metallic calcium, delivered via unassuming wires, acts as a microscopic sculptor and purifier. It doesn’t add massive strength like carbon or corrosion resistance like chromium. Instead, it unlocks the inherent potential of the steel by cleansing its internal structure. For steel companies aiming to compete in the high-value end of the market, mastering this hidden alchemy is not optional; it is fundamental. Calcium is, truly, the unsung hero that transforms good steel into exceptional steel.